http://www.theguardian.com/business/2011/jul/28/habitat-furniture-high-street

A closing Habitat store in Essex. Photograph: Graham Turner for the Guardian

It is a grim Friday morning in Thurrock in Essex: roundabouts in the rain, windswept retail parks, recession-emptied car parks. Half-hidden on a poor site, beyond a huge Ikea branch and half a dozen other homeware outlets, the local Habitat looks forlorn. "Store closing" banners in tacky fat capital letters dwarf the lower-case, still elegant Habitat shop logo. Inside, the chain's usual vaguely Mediterranean furniture and cheery crockery is in undignified, desperate-seeming piles: "All stock reduced!"

Jamie, a nurse in his mid-40s from nearby Upminster, quietly stylish in a red-and-black striped top and suede boots, comes out of the shop with two vast, full carrier bags. "I grew up with Habitat," he says. "My parents went to the original shop in the 60s. It was quite iconic for them." And for him? He frowns: "I haven't got a massive salary. I've always found it pricey, and the quality of the products hit and miss. Some have been great – they did a lovely olive-wood pestle and mortar, I bought loads as presents. But I've often window-shopped in Habitat. I've tended to buy things in sales."

After 47 years, a small eternity in modern retail, Habitat may have finally reached the beginning of the end. Last month, for the second time in 18 months, the core of the business was sold, this time to the British conglomerate Home Retail Group, operator of the slightly less iconic Homebase and Argos. The Habitat website, brand and three best-positioned London shops will survive, at least for now, and Habitat concessions are planned for some Homebase branches; but Habitat's 30 other British stores are in the hands of an administrator, and all are likely to close by the end of the year, if not much sooner.

Habitat has had near-death experiences before: in the early 90s recession for example. Yet this time, with the climate for British retail almost unprecedentedly harsh, and Habitat's traditional core customers – first-time property buyers, students and other young adults setting up home – either disappearing or under terrible financial strain, Habitat's condition is widely seen as terminal. The chain's long association with modern, often foreign design, at a time when fashionable tastes have turned towards all things British and vintage, is also a factor. After its sale to Home Retail Group was announced, Habitat's founder, legendary lifestyle entrepreneur Terence Conran, who has not been involved with the business since 1990, issued a statement: "I'm sad that my love child . . . appears to be dying."

"It's just an almighty shame," says the designer Tom Dixon, who between 1998 and 2008 was Habitat's head of design and then creative director. "The end of an era." With British store chains expiring almost weekly, such declarations about the downsizing of a single, medium-sized one, which employed 732 people at the last count, could be seen as over-theatrical. "Habitat has only made two annual profits since 2001," says Robert Clark, director of Retail Week's Knowledge Bank. Last October, a Knowledge Bank report on Habitat found "sharply declining sales", "soaring staff costs", and a seeming chaos of branch openings and closures, arriving and departing senior managers, head office relocations and emergency cash injections. "In a downturn," says Clark, "there are two sectors of retail that always go bad: furniture and menswear. Customers can postpone their purchases." Habitat, even in its new brutally shrunken form, is lucky to still be in business at all.

And yet, as Dixon puts it, "Habitat still retains a cachet of some sort." Even Clark agrees: "I used to go to the first shop on the Fulham Road [in London]. It was the destination, from the early 60s on, for the younger generation of married people who had disposable income." Online, there is a busy trade in old Habitat annual catalogues: a 1970-1990 set, "a lavish feast of early 70s design [and] onwards", even with four years missing, is being offered for £240.

Among other socially influential products, Habitat has pioneered or popularised duvets and bean bags, woks and paper lanterns, sofa beds and self-assembly furniture, cafetieres and wine racks. It has sold rough-edged Provençal peasant chic and clean-lined continental modernism; wholegrain hippy styles and metallic yuppy ones; idealised versions of both country and urban living; quality goods and disposable ones. Habitat has reflected social change and has also changed Britain – for the better.

With its branches historically concentrated in university towns and near gentrified inner-city suburbs, its story is partly that of the postwar expansion – and now possible contraction – of the British middle class. As a member of the latter, I've been a Habitat customer, not always satisfied, for decades: sometimes its spotlit shops have seemed too hot, its young staff too cool and dozy, its range of merchandise too fixed and flimsy ("Shabitat" is an enduring nickname). But Habitat, as Dixon says, has always been "an organisation based on a lot of intangibles: emotion, taste, snobbishness, aspiration. Paying more than an object is worth is really what Habitat is about." For many Britons, Habitat livened up the previously utilitarian business of home-making with little doses of fantasy, of enjoyment.

For a surprisingly long time, that idea proved commercially viable. When he opened the first shop in 1964, Conran was already a veteran of British domestic design and retail, then characterised by dour furniture stores and a few frustrated, more adventurous spirits like himself. Conran had been to France ("bright colours . . . everything was so simple and beautiful"), and discovered the "stone floors and simple, unpretentious furniture" of the servants' sections of National Trust country houses – refreshingly, the grander rooms on show did not interest him. "I have a taste for austerity and utility," he wrote later, "but that's certainly not to say I have no appetite for pleasure."

The Fulham Road Habitat was in a then-workaday part of west London near a greasy spoon and a pub. But inside it felt like a new world: fresh white walls, cut flowers, piped music (a first), staff dressed in the latest streamlined styles. The fashionable and famous flooded in. "The Duke of Kent got his foot stuck in a fish kettle . . . Kingsley Amis and Elizabeth Jane Howard did their courting in the basement; David Niven was found fighting to get in one day as the doors closed," writes Barty Phillips in Conran and the Habitat Story.

It was not the first shop to offer cosmopolitan modern design at cheap-ish prices: Design Research in Cambridge, Massachusetts, had been doing it since 1953. But Habitat was in a city and a country that was just discovering many of the things – Mediterranean food and travel, the allure of mass-manufactured goods, more informal ways of arranging rooms – that Conran was interested in. "He engaged with the marketplace. He just had that knack," says Clark.

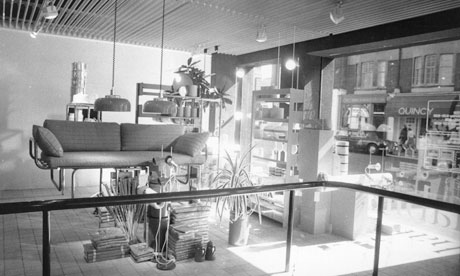

A Habitat store in 1973 Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

A Habitat store in 1973 Photograph: Evening Standard/Getty Images

In the 60s and 70s, young British adults, whether middle-class or working-class, had more money than ever before. In unprecedented numbers, they were buying property, moving away from home to study, cohabiting, taking up DIY. Habitat was on hand to help. After decades of slow urban decay, Britain was full of cheap, vacant retail space; Habitat quickly spread out of London: to Manchester in 1967, Brighton in 1969, Bristol in 1971, Glasgow in 1973. By the mid-70s the company needed a new warehouse to improve its haphazard stock delivery; Conran, ever the showman, commissioned a facility so striking that national newspapers praised its design. When the architects couldn't decide on a colour, Conran told them to match the colour of his Porsche, Phillips records. "He had driven into a bollard and sent the whole damaged wing as a colour sample."

Habitat was in tune with both the materialism and egalitarianism of 70s Britain. In Malcolm Bradbury's celebrated 1975 campus novel The History Man, set in 1972, Barbara Kirk, one half of the book's central, leftwing "modern couple", has "two red canvas bags, Swiss, from Habitat". Even the chain's artful catalogue, with its photogenic young couples and families enjoying bright, unstuffy Habitat-filled rooms, became a status symbol. Sometimes, the catalogue was too forward-looking for customers: when the 1973 edition featured a mixed-race couple in bed, letters of complaint followed.

Conran was a risk-taking, mercurial boss. Even in the late 80s, by which time Habitat had expanded into France, Japan and the US, someone who worked on the catalogue remembers: "He came along to a shoot and had very strong ideas on the styling." His crusading attitude and eye for detail inspired a young, idealistic staff; less helpful to Habitat, sometimes, was his recurring ambition to turn it from a niche into a mainstream retailer. In 1971, after a brief, disastrous merger with office supplier Ryman had unravelled, an accountant hired by Habitat found finances so tangled that: "We had no idea if we were making a profit or a loss."

Undaunted, during the 80s Habitat merged with Mothercare, acquired the famous old London furniture store Heal's and the women's clothing chain Richard Shops, and then merged again, with the department store British Home Stores. The resulting unfocused conglomerate, Storehouse, was far from Conran's original, tightly defined Habitat concept.

Meanwhile Habitat itself began to lose its uniqueness. For almost two decades, it had had little competition: "Habitat seems to have failed to influence other retailers," wrote Phillips in 1983. But then that changed: "Other shops started getting good in the early 80s," says the cultural commentator Peter York, "and one of the reasons was that people who had worked for Conran [at Habitat] went out and set up businesses like him, or gave advice to retailers." They copied Habitat's shop-fitting tricks, such as arranging goods in colourful piles and bunches, which Conran had himself copied from French ironmongers.

In the mid-80s, equally damagingly, Habitat lost its ability to reinvent its range to suit the times. The vogue for aristocratic style, antiques and Georgian pastiche during Thatcherism's triumphant years was difficult for Habitat to embrace, given the company's associations with a more forward-looking, democratic aesthetic. And for Britons who still wanted the latter, 1987 saw the arrival in Britain of a formidable competitor: Ikea.

The Swedish giant was much cheaper and more efficient. By the early 90s, with a recession setting in, Habitat was unambiguously losing money, and Conran had been forced out, thanks in part to Storehouse's labyrinthine internal politics. In 1992 Habitat was bought by Ikea – an undignified but appropriate fate for a chain that had made its name partly by introducing Britons to design from Scandinavia.

The years since have been a struggle, with occasional hints of a return to the glory days. In 1998 the hiring of Dixon, a bold, upmarket British designer who confessed to interviewers he had never bought anything from Habitat, restored some of the chain's originality and ambition. "I did research on what Habitat was like in 1964," he remembers. As Conran had then, Dixon used celebrities and well-known designers to give the shops a whiff of glamour, this time to devise new products. "It felt exciting," says a photographer who worked for the chain under Dixon. "Habitat was becoming a cool design company again."

"I had a few hits," Dixon says. But being owned by Ikea created problems. "We were a pretty small fish. We'd go into a factory used to producing vast volumes for Ikea, and ask for Habitat-type quantities, and we wouldn't be seen as an attractive proposition." Habitat would end up behind its parent company in the production queue. Or it would be suffocated by Ikea's ultra-populist ideas about sales and pricing: "They found it very hard to understand why people would pay more [for an item]."

By 2000, furniture websites were commonplace, but Ikea, ultra-cautious about internet commerce, was reluctant to let Habitat build one. Astonishingly for a high-street retailer, Habitat did not open for business online until 2009. That year, Ikea sold the chain to Hilco, a company restructuring specialist. Ikea and Hilco together spent more than £100m writing off Habitat's debts and providing new investment, but within 18 months Hilco decided Habitat was not a good prospect, and last month dismembered the business.

The decline of Habitat may be a symptom of a certain British postwar expansiveness going into reverse: of young or youngish people who are poorer not richer than their predecessors, who are leaving home later, and who have less faith, perhaps, in the pleasure of shopping and the ability of attractive homeware to make them happy. "The excitement of buying a nice mug – it's gone," says York. "You don't expect to linger. You buy them cheaply and in large numbers."

Dixon still thinks there could be more to mass home retail than the joyless bargain-hunting of a trip to Ikea. "There are so many more people now who are interested in interiors. It feels like there is an almighty big gap in the market." He starts sketching out a shop that sells slick but affordable kitchenware and sounds rather like the first Habitat. Would he consider buying the three surviving branches? "Sure, I'd be interested. But I don't think they're up for grabs."

In one of those shops, a handsome but slightly scuffed semi-basement on Tottenham Court Road that has served generations of north London liberals, the customers are sparse the morning I visit. They are generally middle-aged or older, interestingly dressed, cerebral-looking: the sort of people you see at arthouse cinemas. The Habitat tribe is still out there, but it may not be that large, and it needs new recruits.

But is that a project that interests the latest owners? In a secluded corner of the store, I overhear a conversation between a man in a suit, with an overnight case on wheels and a head-office air – he seems to be one of the new bosses – and one of the staff. "There are two things I think are really missing," says the man in the suit, "some mid-range, really good value product, and some unusual product." It's a long way from Terence Conran and his dreams of Provence.

No comments:

Post a Comment